Past Lives

by Susan

January 1959

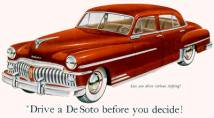

Hutch was still in high school when he bought his first car, a wheezing, rusted, 1950 De Soto that his Aunt Mary sold to him for $100. She wanted to give it to him for his birthday—he was a good nephew, mowing the lawn and doing errands for her—but his father said no, cars were earned, not given. He said that about a lot of things when Hutch was growing up, about bikes and school trips, about sodas and burgers after school at the diner on Route 2. So all through high school, Hutch scrambled for jobs—lifeguard at the country club in the summer, raking leaves in the fall, shoveling snow for the old ladies in town all winter.

Most of what he earned his senior year in high school—before Aunt Mary dangled the old De Soto under his nose like so much candy—got spent taking his girl Darla on dates to the diner and to Saturday night movies at the Palace. The rest went to his books. That fall, he bought a set of the complete works of Alexandre Dumas from the second hand book shop on Fourth Street in Duluth. The set was old, but he’d known the minute he opened The Count of Monte Cristo, the dust rising from each gold-trimmed page, that he had to have it. His father shook his head at the foolishness of spending all his savings on a bunch of old books, but his mother smiled and quietly tucked a five dollar bill in his hand the next morning before he ran to catch the school bus.

When his Aunt Mary offered to sell him the car, big and blue and with enough chrome to outfit a hundred bathrooms, he had to tell her—hands in his pockets and dragging one shoe across the braided rug in her living room—that he had no money to buy it. She offered a payment plan, ten dollars a month for ten months, but his father said no to that too. Hutch would’ve been happy if he’d just said “no” and left it at that, but nothing was ever that simple in the Hutchinson home. Instead, he received a lecture about the evils of credit and the sin of living beyond one’s means.

While his father talked, Hutch imagined how he might finally convince Darla to do “it” with him if he could offer her the enormous back seat of the De Soto to do it in. He imagined her dark hair fanned out against the cracked white leather, her bare legs wrapped around his hips . . . His father ended that fantasy by stating that the car would stay with Aunt Mary until Hutch had the money. Hutch retreated to his room, and between cold showers and long visits to the bathroom, between reading The Three Musketeers and wishing he was old enough to leave school and get a real job, he worked on a plan. One that would let him earn the most money in the shortest time, and that would get him the car before Darla lost interest and decided to offer her virginity to Billy Bracken instead of him. Billy’s father owned a shiny new Cadillac, and Hutch knew that loyalty and devotion were not two of Darla’s best qualities. He was familiar with Darla’s two best qualities, having been allowed to slip one hand under her blouse at the movies one Saturday night during the long chariot scene in Ben-Hur.

He printed purple flyers—offering his shoveling services for a small fee—on the school mimeograph machine after class. He folded them neatly and stuffed mailboxes every day after school for a week. Then it didn’t snow for a month—a record in Duluth. Darla was busy a lot that month—“band practice” she explained, looking away. She wasn’t much good at lying either.

Next, he put an ad in the school paper offering math tutoring to anyone who could pay. The only person who answered the ad was Rocky Finnegan, a senior whose idea of tutoring turned out to be paying Hutch fifty cents to do his algebra homework for him. Unfortunately, the math teacher—one year away from retirement and living in a haze of gin and smoke—didn’t give Rocky enough homework for Hutch to earn bus fare, never mind a car.

When he saw the ad in the back pages of the women’s section of the Duluth News-Tribune, he paid his sister a dollar that he didn’t have to call and apply for him. She knew she’d only get the dollar if it worked, so she did her best to sound older than fourteen. She nearly broke into a giggle when the man said she could start the following week, but Hutch waved a finger in her face and tried to look stern like his father, and she took a deep breath and said, “thank you ever so much” in a tone that sounded so much like his mother it gave him a chill. The sample package arrived two days later, along with a box of catalogues and order forms and an instructional booklet on selling and demonstration techniques.

Each afternoon after school, in his white shirt and Sunday pants, sample case slung over one shoulder, he’d ring doorbells in the part of town where no one knew his parents, and say “Avon calling!” when the front doors cracked opened. The women, sweaters pulled tight against the cold, would laugh at first and ask if it was a joke, but he’d smile shyly and answer, “no m’am.” He’d sigh and lower his sample bag to the ground like it was much too heavy for someone as young as him to carry.

Most times they’d ask him in and offer him a snack while he set up. He’d sit in living rooms, perched on the edges of identical velveteen sofas, and demonstrate the new line of face powder or mascara or hand cream, while the women’s children played in the next room. He’d leave lipstick samples and small envelopes of perfume behind, and take orders for bath salts and talcum powder and eye shadow. Sometimes a housewife would hint she was interested in more than the catalogue, but he was too scared and much too Protestant to take them up on these offers. He made twenty percent on each sale—fifteen percent for him and five percent for his sister’s silence. Which was relative, the bribe stopped her from telling his parents, but not from chanting “Kenny is an Avon Lady” under her breath every time he passed her in the hallway.

In three months, he had enough to buy the car. He picked it up one Sunday afternoon after church and drove it straight to Darla’s house. The clutch stuck and it coughed and sputtered a few times, but he didn’t care, it was his. But when he pulled up out front, he saw a shiny white Cadillac already parked in the driveway. He recognized the Grand Canyon bumper sticker on the fender—the Bracken family vacation the previous summer—and knew he was too late.

When his father asked him later how he’d earned the money for the car, Hutch told him he’d sold the Dumas books to a collector for a profit. His father looked pleased, but Hutch suspected his mother knew the truth—part of it anyway. Hutch hid the books under a floorboard in his closet, and re-read The Three Musketeers late each night after everyone had gone to sleep. While he slept, he dreamt of Darla and all the other things he wanted but could never have.

July 1979

Light fell through the bedroom window in angled shafts, collecting in pools on the floor. Hutch stood by the bed and checked on Starsky—still sleeping, his breath soft but real against his fingertips.

Starsky eyes opened slowly. He turned carefully in the bed and swore. “I can do it,” he muttered, when Hutch bent over him to help.

Hutch recognized his fierce determination, the way it covered his fear, and moved away.

“Just fix my pillows. They’re flat again.”

Hutch pushed away his own fear. “Pillow fluffer. My childhood ambition fulfilled.” He lifted Starsky’s head and held it against his chest as he rearranged the pillows, then kicked off his shoes and lay down beside him on top of the covers.

“Talk to me, Hutch. I’m bored.”

“You’re supposed to be napping,” he answered, then his face softened for a moment, the frown of worry easing from his forehead. Bored was a good sign, the doctor had said. “You’ve heard all my stories. Tell me one of yours.”

Neither one spoke for a few minutes, then Starsky started to talk. So quietly that Hutch had to lean in to hear him. “I used to go the country with my cousins every summer, up in the Adirondacks, north of the city. Nicky and I would run wild through the woods every day. I loved it.”

Hutch smiled and raised one eyebrow.

“Okay, so I sort of exaggerated when we went to the Captain’s cabin. It worked, didn’t it? Anyway, the first summer after my father died, before I came out here, we found a deserted cabin. The windows were all busted out so the wind made strange noises as it blew through. My cousins told us it was haunted, but I didn’t care. It was like my secret place after that. I would sit there for hours, think about my father and dream about what my life would be like.”

“You didn’t dream this,” Hutch said, looking over at him.

“No,” he said softly. “Never this.”

After a minute, Starsky said, “Okay, your turn. Tell me something I don’t know.”

He took a breath. “I was an Avon Lady when I was in high school.”

“Bullshit.” He yawned through his smile.

“It’s true. I needed money to buy a car. See, there was this girl, Darla . . .”

But Starsky was already asleep.

~~~

June, 2007

This story was a response to a discussion on Me and Thee about whether Starsky and/or Hutch had any secrets in their pasts.